|

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in these articles are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Wrestling-Titles.com or its related websites.

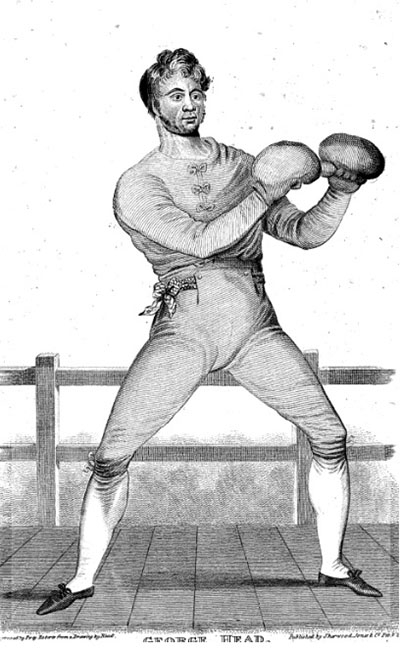

"The Inimitable George Head,

or It’s Feytin’ not Rosslin’!"

"I don't like Yorkshire fighting; hugging, biting, and kicking, does not suit me.”

Foreword

by Ruslan C Pashayev

In my book The Story of Catch (2019), and in some of my articles (such as Lancashire Catch as catch can, Pioneers’ Catch, and etc.) I mentioned the infamous Lancashire way of fighting (or a “no-method” as it was often called in contemporary English sporting press), which not only included fighting with fists, a proper pugilism, but also allowed “kicking, wrestling and throttling” your opponent. Another important detail about that style of fighting was that it was “Ok” to attack a person who was already down, so to say it was not a fair or stand-up fight, you could kick into unconsciousness a person who were helplessly laying on the ground, it was totally fine, and not just that, you could fight them in horizontal position, rolling on the ground for the par-terre dominance, and then after achieving the “mount” throttle them and punch them if necessary, all these were approved strategies in this so-called sport. Often time such disgusting methods as pulling hair, head-butting, biting, tearing noses and mouths as well as gouging played important role in obtaining the desired result in those unregulated contests. As a matter of fact “all was in” in the desperate attempt of making your adversary shout “I yield!”

Unfortunately many authors of the past confused two “manly” sports of Lancashire miners (and weavers) the so-called “shin-kicking” matches (aka purring or puncing contests) and the up and down fighting. That happened because both those brutal pastimes of the old incorporated kicking, or purring an opponent, and not all of the writers actually witnessed either of these two sports to make a fair judgement, so they heavily relied on hearsay, which often time was nothing but misleading.

The most detailed and accurate account of Lancashire fighting is presented by the famous writer called Samuel Bamford (1788-1872), who was a native of Middleton, Lancs. We can trust his writings and his expertise in this subject, because according to him, his own father was a proficient up and down fighter, and the author himself many a time witnessed those bloody exhibitions. I included his “up and down story” and an extensive commentary by another author in this article.

All Goes In. From “An Illustrated Itinerary of the County of Lancaster” (1882) by Thomas Pitt Taswell-Langmead.

“A different species of country soon opened before and around us. On our left, high and barren hills ran up, then expanded into moors, with here and there a clump of poor stone cottages by their side, or a sort of substantial house, also of stone, erected in the bottom, but in a bleak situation, and being in reality as cold as it looked. On our right ran the Irwell, which, taking its rise in the high country of which we have spoken, runs through a picturesque vale by Haslingden, Bury, Bolton, and falls into the Mersey below Manchester. We were on the point of entering Haslingden, when a sudden "hurrah! bravo!" burst around us, and called off our attention from a beautiful view we were contemplating in the vale below. The coachman at the same time pulled up, and we perceived, a hundred yards in advance, a number of rude-looking people intently and silently beholding two men, who were grappled and locked in each other, leg with leg, arm with arm; now lying as still as death, now rolling with fearful struggles on the high road. It was, we saw, a Lancashire fight; and a Lancashire fight is something far worse than the Pancratium of old. The native peasantry know nothing of boxing, as such. In their quarrels they literally fall foul of and maul each other in every possible manner -with the fists, teeth, and feet. Instances have been known in which a nose has been lost, or a rib broken, or a jaw knocked in, during the scuffle. We ourselves once saw a brutal fellow, after having mastered his antagonist, and rescued himself from his gripe, jump suddenly on his legs, and begin to kick his ribs with his huge wooden clogs. The subject has been sketched by one who, to the advantage of a life passed among these people, unites an easy, flowing, and graphic style. Let Bamford, the Middleton poet, describe to our readers the details of a species of conflict with which few of them perhaps are familiar. The passage is extracted from his interesting and, by snatches, poetic little volume, entitled "The Life of a Radical," a work which ought not to be limited to a provincial circulation.

"The combatants were our friend the poacher, and another man, younger and heavier, who chiefly earned his living by dog breaking, and under-strap- ping to gamekeepers and their masters. Betwixt the men there had been an unfriendly feeling for some time, and now, over this potent ale, for it was good though new, their hostility was again excited and probably decided. The ring was formed with as much silence as possible. The men stripped to their waists, and then kneeled down and tied their shoes fast on their feet. They then dogged for the first grip, much as game cocks do for the first fly; and after about a minute so spent, they rushed together and grappled, and in a moment the dog-man gave the poacher a heavy kick on the knee, and was at the same time thrown violently on the ground on his back, his antagonist alighting on him like a bag of bones. It was now a ground fight for some time, and exhibited all the feats of a Lancashire battle, which I take to have been derived from a very remote date, long before the Art of Self-defence," or indeed, almost any other art was known in these islands. There was not, however, any of that gouging of the eyes, or biting the flesh, or tearing, or lacerating other parts, which are often imputed to Lancashire fighters by cockney sportsmen and others, who know little about them. It was all fair play, though certainly of a very rough sort, and as thorough a thing of the kind as I had ever seen. Doggy, after gaining breath, tried to turn on his belly, which Poacher aimed to prevent, pressing the wind out of him by his weight upon the chest as he lay across him, and, at times, throttling him until his eyes started as if they were looking into another world. In one of those suffocating agonies, Doggy flung round one leg, and locked it in one of his opponent's, and in a moment they were twisted together like the knot of a boa constrictor; and the next, Doggy turned on his belly, and got on his knees. There was a loud shout, and much cursing and swearing; and several bets were offered and taken as to the issue of the contest. Poacher now laid all the weight he could on Doggy's head and neck, to prevent him from getting upright. He grasped him below the arms, and kept clutching his throat; and the latter, for want of breath to carry on with, kept tearing his hands from their gripe; both snorted like porpoises, and it began to appear that our friend Poacher was the worst for wind. Some heavy kicking now ensued, until the white bones were seen grinning through the gashes in their legs, and their stockings were soaked in blood. Poacher was evidently a brave man, though now coming second; in one of his struggles, Doggy freed himself, and rushed on Poacher, with a kick that made the crew set their teeth, and look for splintered bones; and Poacher stood it, though he felt it. There was another clutch, and a sudden fling, in which Poacher was uppermost, and Doggy falling, with his neck doubled under, he rolled over, and lay without breath or motion, black in the face, and with blood oozing from his cars and nostrils. All said he was killed."

Based on this vivid and meticulous description of the Lancashire method of fighting we can summarize the above by almost citing a quintessential statement of an unknown 19th century sports writer, by saying: “Lancashire fight is (meant to say, was) an ugly sight…” Interestingly, this particular fight, from the Bamford’s “Radical” was decided by a heavy fall of one of the contestants on their neck, a knock-out finisher which I assume (with an irony) could have qualified as a “very fair back fall”.

Outside the towns and cities of Salfordshire and Blackburnshire in Lancashire County this “barbarous method of pugilism” (I am using a proper Victorian terminology) was also practiced in the neighboring West Riding of Yorkshire where it was obviously known as the Yorkshire Fighting. And you figured my dear reader, all that was happening “long before MMA”! What nowadays became a norm and is even widely considered as a sporting phenomenon, I mean a no-holds barred fights, in Victorian England was thought of as an expression of ferocious animalistic instincts which dwell deep in human’s nature, a sort of an abomination.

Some of the references by various authors on this matter are to follow farther in this article, among which there is an interesting account of the early 19th century pugilist called George Head who at his prime was considered the peerless exponent of the up and down style of fighting in England. Enjoy the read my dear friends.

“YORKSHIRE FIGHTING. From Mr. RYLEY's, "Itinerant".

At length the company were summoned into the barn, to witness a battle between two noted Yorkshire fighters. Amidst the crowd I perceived two men naked to their waists lying on the ground, grappling each other. perfectly silent, and sometimes pretty still; then, as if moved by one impulse, a desperate scuffle took place; soon, however, the one extricated himself, quickly obtained his legs, and retreating some paces, returned with great violence, and, before his antagonist could rise, kicked in three of his ribs: the vanquished lay prostrate, whilst the victor stamped and roared like a madman, challenging all around. Retiring to my seat in the house, disgusted with Yorkshire Fighting, I determined to finish my wine, and leave the brutes to the enjoyment of their brutality, when a laughable circumstance detained me, and in some measure made amends for the misery I had suffered.

There is, I believe, a respectable personage, who, amongst amateurs in sporting, bears the appellation of a Belward, a gentleman who gets his livelihood by leading a bear by the nose from village to village; such an one now arrived at this public house, and placing his companion in the pigsty, seated himself by the fire, and called for a pint of ale. The Yorkshire warrior, elated with his victory, and intoxicated with liquor, went from room to room, and bad defiance to every one; on entering the kitchen, he espied the Belward, who, being a stout fellow, and a noted pugilist, was immediately requested to take a turn with him- No, no," replied the stranger, "I don't like Yorkshire fighting; hugging, biting, and kicking, does not suit me; but I have a friend without who is used to them there things: if you like, I'll fetch him in?" "Aye, aye, dom him, fot him in: I'll fight ony mon i'th' country." The Belward repaired to the pigsty, and brought forth Bruin, who from a large sized quadruped, was changed instantly to a most tremendous biped. In this erect posture he entered the house, and as it was nearly dark, the intoxicated countryman was the more easily imposed upon-" Dom thee," he said, "I'll fight a better mon nor thee, either up or down," and made an attempt to seize him round the middle, but feeling the roughness of his hide, he exclaimed-" Come, come, I'll tak no advantage; poo off thy top coat, and I'll fight thee for a crown." The bear not regarding this request, gave him such a hug as 'tis probable he never before experienced; it neary pressed the breath out of his body, and proved, what was before doubted, that there was as great a bear in the village us himself.”

The Fighting Habits of Virginians?!

From History of the United States of America in 1801-1817, Vol 1, by Henry Adams (1889-1891).

“Virginians with fondness for horse-racing, cock-fighting, betting, and drinking; but the popular habit which most shocked them, and with which books of travel filled pages of description, was the so-called. rough-and-tumble fight. The practice was not one on which authors seemed likely to dwell; yet foreigners like Weld, and Americans like Judge Long- street in "Georgia Scenes," united to give it a sort of grotesque dignity like that of a bull-fight, and under their treatment it became interesting as a popular habit. The rough-and-tumble fight differed from the ordinary prize-fight, or boxing-match, by the absence of rules. Neither kicking, tearing, biting, nor gouging was forbidden by the law of the ring. Brutal as the practice was, it was neither new nor exclusively Virginian. The English travellers who described it. as American barbarism, might have seen the same sight in Yorkshire at the same date. The rough-and- tumble fight was English in origin, and was brought to Virginia and the Carolinas in early days, whence it spread to the Ohio and Mississippi. The habit attracted general notice because of its brutality in a society that showed few brutal instinets.”

The Styles of English Boxing and some more. From Boxiana for the years 1821, 1822, 1823. Vol. IV (1824).

“This is precisely the sort of education adapted to form the best fighting men, early habits serving us, in every case and at every emergency; and if to such early manifest advantages they add those of having overcome sturdy opposition, and of having outwitted artful contrivances for obtaining those juvenile victories, they thereby fashion a plan or school of themselves, in which may be discovered each individual's characteristic mode of fighting; and which partakes invariably of the method pursued by those he has contended with, or observed approvingly while fighting. Thus we have the Bristol method, the Broughton method, the Staffordshire, and the Lancashire methods, or no method. Each man invariably adopts the peculiarities in any of those methods or manners of fighting (we hesitate to call either "a system") that may seem, or be found by him best adapted to his own particular powers, and notions of the fit moment of attack, and the right point to be hit at.”

THE INIMITABLE GEORGE HEAD.

“Why about pugilists this pother? These first shake hands before they box; Then give each other plaguy knocks, With all the fondness of a brother.”

THE man who, in the exercise of an Art (no matter what), is hailed by the general voice as the inimitable of his particular profession, could not fail, in an age like the present, to attract towards himself the kind regards of congenial souls. The Press alone did not do justice to the fame of GEORGE HEAD until a very recent period; by reason of those who influenced its direction belonging mostly to the slashing and hammering sect of boxers. But Pugilism or Boxing would be nothing in our sight, were it not for the combination of talent and fortitude which it is necessary the combatants should possess, in order to make a prominent figure in the area which has been denominated "the Ring." It would be worse than nothing, and intolerable, nor be allowed to exist in the land, from its tendency to degrade the mind, if disconnected with those who study the art of defending themselves as well as inflicting punishment upon the adversary; and who, by thus bringing into operation the faculties of the mind, form a class of boxers differing totally from the slashing and ruffianing class, who possess neither mind nor conduct, nor the ordinary suavities of life in its commonest concerns. It is this which alone renders it palatable to the great men and scholars of our time; and, but for this circumstance, we have no hesitation in saying-its practice would have been put down several years since by the dominant party of puritans, who carried before them almost every other point of attack on the national characteristics.

Bending somewhat to the ill-taste of the times, the public notices bestowed upon all mere pugilists of the day just gone by-those who knew how, but who little practised-were few and scanty; some of them in their exhibitions at the Fives Court were even reprobated for the simple exemplification of the Art, as an art, with the mufflers on their mawlies, and the absence of HEAD was in like manner sneered at, as the effect of something criminal. These surmises, regarding him, at length got into form, and were promulgated in the choking shape of a suspension at the York drop, for a rape! A very candid and cordial sort of finish to a man's career, that might have been exploded by setting afoot the least spark of inquiry. One of the journals devoted to the Fancy did, indeed, insert the following advertisement after him, which serves to show that he was an object of interest, at least, to some of the better sort of ring-goers :-

"GEORGE HEAD.-Can any of our Readers tell us where about he is at present? If this meet his eye, we should be very happy to receive a communication from him. The last we heard of him was that he taught our Art at Hull, in Yorkshire."

This insertion produced the desired effect of an indirect communication from a portion of his family, and the result proved, that, although an error existed as to the town, he yet sojourned in the West-Riding -where he had seen some service in the way of Pugilism, without seeking after the job-as we shall presently show.

But the neglect, just adverted to, began at a much earlier period than the developement of his sparring excellencies; this was his first or maiden battle with Bully Hooper, in September, 1786, at Bartholomew Fair. Hooper was well known for the many stiff fights in which he had been engaged, and he was the terror of most men in street or ale-house, where he would not hesitate to empty the glasses of the guests, and knock down the first man who grumbled. This battle, which arose out of some such an incident, lasted about a quarter of an hour, when Hooper re- signed the contest; and GEORGE HEAD was induced from that moment to cultivate the Art-with how much success, remains to be shown.

The immediate cause of his going into that county was in consequence of an invitation from a pupil who travelled the north country in the way of trade, and who, having taken umbrage at a countryman, staid in the vicinity of the yokel's residence (Black Barnsley) until the hour of fighting arrived. This was fixed for the 2d of April, 1819, and HEAD having reached Barnsley ten days before, hastily set about preparing Green to tackle his big opponent. Short as was the notice, the time seems to have been fully improved upon; and, short and thick as was his pupil, GEORGE contrived to make him beat his overgrown opponent, Wike by name. For the hand he had in effecting this desirable purpose, the aid and assistance he afforded to Green, in the capacity of his second, and the consequent losses sustained by Wike's supporters, who judged more by size than science, brought down upon GEORGE HEAD the coarsest maledictions and threats of the losers-some of whom were half ruined by the unexpected upshot of the fight. To us, however, to HEAD, or indeed to any person who carries a tolerable degree of nous into the inquiry, there is nothing very wonderful in mind overcoming matter; in a man of less than ordinary stature, with a knowledge of the points to be hit at, and those he should defend, getting the best of a great slashing fighter, who would slobber away and almost beat himself, as in this case: accordingly, he heard their vituperations unmoved- they considered him (truly) the cause of their losses, in particular, for not permitting the men to fight "country-fashion, up and down, kick, b-, and bite;" and they accused him of having in this manner cheated, swindled, and robbed them of their bets. "Ahh, Ach! Dom thou, thee G dom'd GEARGE YEDS, thou to-ad on a swindler, I'll bray thy brains out, thou gre-ey-yedded pickpocket fuil thou"-is a tolerably fair and literal specimen (copied ad vivam) of their indulgence in local slang.

Our "Lunnun cheat," however, felt little inclined to "run the country," as thus incited to do; the odds being (if we know aught of the man), that those pretty, amiable speeches, delivered with all the grace, elegance, and dentical energy of those parts-constituted the main cause of his sticking to the spot- "just to see what the devils-alive would try to do." Long time he suffered under this obloquy-if the dirt thrown by such beings (scarcely human, however rich) may rank so high as to deserve a name, when the 18th of August, 1819, brought on the pretty little fair of Westborough, four miles from Barnsley, and with it a specimen of Boxing versus Pugilism, little known in the West Riding, or indeed in either riding, rape, or wapentake at that part of the island.

Like most provincial towns, Barnsley had its dominant boxer, or bully-the local champion of the neighbourhood, who had put down all thereabout by dint of hard knocks and bold threats-his name, Jemmy Gibson. This fellow was selected, by one of the losers in the affair of Green and Wike, to revenge the empty clies his employer had been reduced to upon that occasion; and although four months had passed away since that event, the rancour then engendered rankled still, and Jemmy Gibson was employed, at an expense of two guineas, to take it out of GEORGE HEAD. For this task he was fully competent, so far as quantity and bottom goes, about fourteen stone and a half against ten stone two pounds being fearful odds; and if our hero, GEORGE, proved himself lion-hearted in tackling such a mass as Jemmy, no less so was the latter in putting up with the terrific and reiterated chastisements he received from the hands of GEORGE HEAD; a punishment from which he has not recovered to this day, and from which he never will be free, probably, until the day that his immaterial is set free from the material part of him.

On the 18th of August, 1819, did Jemmy seek for GEORGE up and down the fair of Westborough, provincially termed "Wesper feast," and finding him walking in the company of some respectable females of the place, his first insults were treated with the contempt they merited. This but farther increased the brutal insolence of Gibson, who proceeded from one insult to another, until he followed HEAD ready stripped for the fray.

First round. They met at the door of Head's quarters, a public-house, before which they fought; Gibson stripping very fine, Head reduced in consequence of having lain up with a broken leg; however, he threw away his crutch, and they set-to. The crouching of Gibson seemed as if he would claw his antagonist, and tried to catch hold, when Head hit out, right, slanting upwards, whereby Jemmy was floored on the pebbles, receiving a couple of remembrancers as he went down.

Second. On coming up, Gibson gave an ugly proof of Head's mode of tattooing: the cartilage of his snout was driven up so as to protrude through the skin, nearly between the eyes; the claret flowed in a perfect curve, the lower part of his nose being laid quite flat. Gibson might be said to sparr, unless we ascribe his present caution to fear of his opponent's terrific right hand, when whack! he caught another hard one upon the old spot (Bristol fashion); the force threw him back against the house, and he rebounded upon Head, who was run off his pins right into the middle of Wike's confectioner's stall. Here they both lay, covered in all the varied sweets of such set-outs, the whole of which was rendered a complete wreck by this manoeuvre of their friend Jim.

Third-Being brought forth to light, it was found that the men had been settling matters in the dark, the one as pay-master, the other as receiver-general. Head being undermost,

was pinned to the ground by Gibson (it seems); but getting an arm free, he hit away at the head repeatedly, until Gibson was scarcely to be recognized. But still, with a heart not to be so daunted, he came up again, and was again knocked down.

Fourth. At being placed, Gibson bore a piteous spectacle, emaciated, pale, and all abroad; whilst Head, whose face was besmeared with his antagonist's claret, which adhered to it whilst on the ground, showed little the worse. However, "Go it, Jemma Gebsen, fettle t'me-outh o'tha b- and the recollection of the reward he would receive, re-in- spired the bawbuck; but he scarcely exchanged blows, when he was again knocked down.

Fifth to about twenty-five rounds.A repetition of detail which included nothing beyond the knock-down arguments of Head, which concluded every round; and that Gibson was all abroad, like a ship at sea without compass or rudder, would prove most tedious and dull. It lasted forty minutes.

REMARKS.-Never was man more punished, perhaps, certainly none ever so disfigured as this one; his loss of blood, too, must have been immense, for when both men lay on the ground above a minute, the blood of the beaten man ran into the eyes, ears, and even mouth of HEAD as he lay or turned underneath his bulky opponent. This thrashing bout, however, left but a small impression on his heart, notwithstanding the marks on his visage; for Jemmy Gibson would needs try another suit with his former antagonist, and on the first of January following, 1820, he again sought the hand of Head, and again tasted of his prowess.

They fought this time for ten pounds a-side, in the room of a public-house in Barnsley, where four stout companions of Gibson were admitted to see "fair play, Yorkshire fashion, up-and-down;" for the brutes would have it so, notwithstanding the remonstrances of GEORGE HEAD and the gentlemen present, with whom GEORGE had been taking dinner.

As before, the present battle was brought about by Gibson's bitter execrations, and seeking for HEAD up and down the town; but a contest carried on upon such principles, or rather no principles, is not to be described with the usual temper attendant upon a regular mill.

One round would have settled the hash of either of the two brutes, in an ordinary Yorkshire fight-or, as we have it in London, "the Lancashire fashion;" but HEAD found himself tired of punishing his brutal opponent, and gave over for wind six or seven several times-though he knew it was allowable for him to have tumbled down upon the great beast, and there upon the floor tore out his eyes, bit off his ear, nose, or thumb-or all three; but in this species of conflict he well thought the odds were against him.

Twice did Gibson turn quite round from the severity of the sarvices; and under the expectation, probably, that HEAD would lay hold, he run his head into a corner, but the latter stood off and floored him. Once he sat on the ground, and in that position proved himself a fine receiver, scarcely putting up his hands to screen his face, which was now again grossly disfigured; but he seized the leg of GEORGE HEAD, and fell backward with it, intending in that manner to finish the battle, if not his victim, by gnawing off some precious part or other of him. From this herculean grasp, however, HEAD escaped by a sudden jerk, that proved effectual, by reason of the warm claret that rendered the paws of the beast slippery; and, in the effort, GEORGE's toe met the chin (underneath) of Jemmy, which his four companions declared "all fair and right," and excited their favourite to retaliate in the same way. But we stop the pen-it is an appalling duty which compels the description of such a scene to its full extent; for we have scarcely more than alluded to the unbearable attempts of the big ruffian, who was at length induced to cry "I yeald," and resigned the £20 stakes to GEORGE HEAD.

Of his more remote turn-ups with Gregson and with Reynolds (see Boxiana, vol. ii. pages 431 and 486), a few particulars may not improperly be added here. With the first named (a Lancashire man) he stood up nine rounds, knocking down his great big opponent every time, and to so much purpose, that Bob Gregson voluntarily retired out of the room, quite satisfied; a very appropriate kind of exit, viewing the manner of its commencement, which was by the big-one's knocking HEAD out of his chair, without notice-Lancashire fashion. "Do you mean that, Bob?" asked GEORGE. "Ah, marry, a' do mean't, and, dom tha', I'll foight thee," replied Gregson, taking off his blue squeeze- wipe, and tying it round his waist. The result is known.

With the warm-hearted Reynolds, three bouts, with the gloves, took place in the room of the latter, HEAD being well known to all present; the fact could not possibly be otherwise, as HEAD had but recently left the same roomy premises, viz. No. 9, Fleet-market, wherein he had been immersed four years, for a balance of fourteen shillings only, besides costs of suit. These he had recently paid in full, but often went in to see his acquaintance, and upon one of those occasions this oft-repeated rencontre, in two acts, was performed. As to the room-affair, and Mrs. R.'s tearing the skin off HEAD's face, nought more need be said than to notice the pleasing occurrence; but Tom Reynolds was induced to follow GEORGE into the racquet ground, where the latter was at play, challenging him to fight. Two rounds only were actually fought, in both of which Reynolds caught the well-directed sarvices of HEAD, and floorers for conclusion of each, coming down in the second between the feet of HEAD. No time could be found for more rounds (as said); such exhibitions being disallowed in the Fleet, and the turnkeys soon took HEAD into custody, he not being a legal inhabitant there. In this position Reynolds found HEAD's head very much at his service: he certainly made the most gallant use of the opportunity thus offered, and gave it him well all the way to the door of the prison, where Reynolds made use of his interest to get HEAD refused a re-entrance, and a good judge too.

As a teacher of the fistic art, HEAD ranks at the very top of the list; his mode of instruction having in it scientific arrangement and progressive improvement, on the easiest and most facile plan we are yet acquainted with. Distance he measures well by a method peculiarly his own, as it includes straight and rapid hitting, and getting away at the same time; bottom he deems inherent, or that it must improve with the consciousness of superior skill; activity he thinks is to be acquired by practice and training, and this latter prelude to boxing engagements he carries on much on the principles laid down in the earlier pages of this volume.

Great versatility of talent is found in "the inimitable" GEORGE HEAD; who, like "the admirable Crichton," is passing out of life (as we may say, being now fifty-four years of age) before full justice be done to his memory and achievements. A tailor by trade, he has rescued the calling from the vulgar aspersion, which is as untrue as 'tis impertinent; he is not only a good fit in this and the other line, but formerly invented the patent coat, with a single seam. He is also not only full of life, ardour, comic anecdote, and song, but writes well in verse as well as prose; in both excelling all who, during his time, have attempted to write and publish on any boring affairs-if most of them did not employ other heads and abler hands than their own to indite their epistles and poetic effusions." His chaff and gig render HEAD a truly "inimitable" bonvivan companion; and his Sunday evening's levee is attended with all the variety that an hilarious assemblage of "All the Family," with copious drains of fuller's earth, can inspire. Some of “the family" turning a line of Cross's song, applied it to HEAD:

“Of boxing sure none ever was prouder, He'd tip a chaunt, run the rums, Chaff a tale, queer all bums;In its praises no cove e'er was louder.In its praises no cove e'er was louder.”

Ruslan C Pashayev is an expert-member of the Traditional Sports Team of the Instytut Rozwoju

Sportu i Edukacji

(the Institute of Sport Development and Education), Warsaw, Poland.

© 2023 Ruslan C Pashayev All Rights Reserved.

|